A leap is made but the microbe remains benign in its new host, as it was in the old one (Simian foamy virus?). “Sometimes nothing happens,” Epstein said. The new host might be any animal but often it’s humans, because we are present so intrusively and abundantly. “It increases the opportunity for these pathogens to jump from their natural host into a new host,” he said.

But when we humans disturb the accommodation-when we encroach upon the host populations, hunting them for meat, dragging or pushing them out of their ecosystems, disrupting or destroying those ecosystems-our action increases the level of risk. They have reached some sort of accommodation, replicating slowly but steadily, passing unobtrusively through the host population, enjoying long-term security-and eschewing short-term success in the form of maximal replication within each host individual.

They have coevolved with their natural hosts over millions of years. They don’t necessarily cause any disease. “A lot of these viruses, a lot of these pathogens that come out of wildlife into domestic animals or people, have existed in wild animals for a very long time,” he said. Repeatedly over the next half hour he returned to the word “opportunity.” It kept knocking. It’s a matter of contact with humans, interaction, opportunity. You can’t look at a new bug or a reservoir host, he said, as though they exist in a vacuum. “The key is to understand how animals and people are interconnected.” We were back at the hotel, showered and fed, after another full night of trapping, another fifteen bats sampled and released. I had accompanied him on a fieldtrip to southwestern Bangladesh in search of evidence of Nipah virus. He is a veterinary disease ecologist, employed at the time by an organisation called the Wildlife Trust (now, EcoHealth Alliance). “The key is connectivity,’ Jon Epstein told me. This was not from prescience, but from listening to the right scientists.

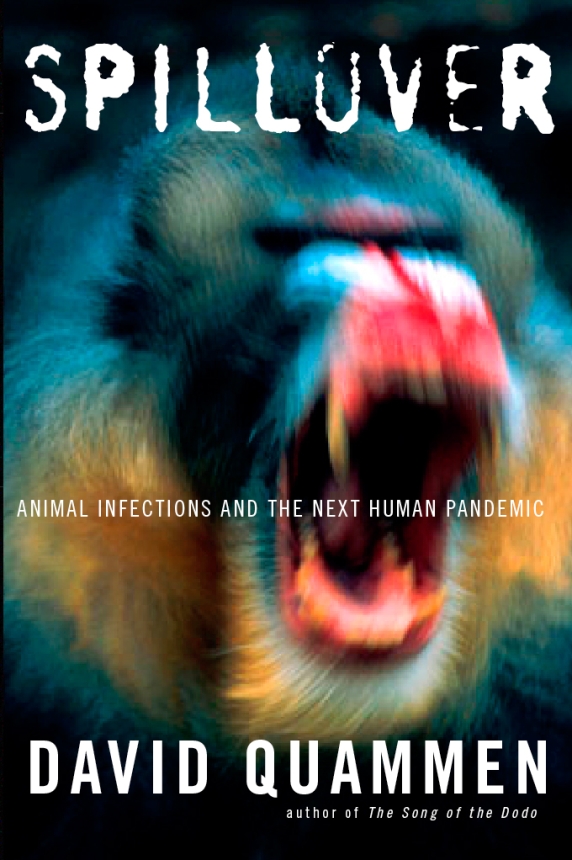

Back in 2012, I predicted in my book Spillover that a novel coronavirus could prove to be the Next Big One. Prior to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused it, I traveled the globe to better understand the devastating potential of animal infections transmissible to humans. Aiming to foster the fruitful exchange of expertise and perspectives across fields to help us rise to this critical challenge, opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the OECD. This excerpt is part of a series in which experts and thought leaders - from around the world and all parts of society - address for the OECD the COVID-19 crisis, discussing and developing solutions now and for the future. Used with permission of the publisher, W. Adapted from Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)